© 2019 Natalia LEBEDEVA

2019 — №1 (17)

Citation link:

Lebedeva N.D. (2019) Institutional Frameworks for Psychiatric Treatment after Health Care Reforms. Medicinskaja antropologija i biojetika [Medical anthropology and bioethics], 1(17).

Key words: mental health care, mental health services, health care professionals, deinstitutionalization, psychoneurological center, rules, actors, institutions

Abstract: The article contains the main characteristics, similarities, and differences of institutional frameworks of psychoneurological centers (dispensaries). The author considers issues of the relationship between formal and informal rules, professional and institutional social norms, and the relationship between the nature of relations (authoritative or collegial) within the organization and the mediated relationships outside it. The study of institutional frameworks is based on in-depth interviews with high- and mid-level medical staff. The analysis takes into account the difference between psychiatric institutions in Moscow and the Moscow region, as well as between the psychoneurological centers in Moscow which are subordinate to different psychiatric hospitals.

Author info:

Natalia Dmitrievna Lebedeva – MA in Sociology (The Moscow School of Social and Economic Sciences / The University of Manchester); Independent researcher. E-mail: n.dm.lebedeva@gmail.com

*The research was supported by the Oxford Russia Fellowship 2018-2019

The article presents the results of qualitative research of social orders of psychiatric institutions. The aim of this research is to reveal the main characteristics, similarities and differences of institutional frameworks of psychoneurological dispensaries (this form of ambulatory mental health services exists only in Russia and other CIS countries). The analisys of the local social orders, in turn, will allow to understand the changes in the organizational field that happen as a result of large-scale psychiatric reforms.

The processes that are taking place in the field of psychiatric care today bring to the fore the issue of the functioning of formal directives within individual organizations. In this regard, psychoneurological dispensaries are the most spectacular cases. Psychoneurological centers are subordinate to the hierarchical structure of institutions that control the quality of public health services (Ministry of Health, territorial funds of compulsory health insurance, asylums or government health clinics). In addition, dispensaries are a link between the various institutions (psychoneurological boarding houses, social protection services, law enforcement agencies, military service). They are part of an extensive network of organizations with different systems of institutional rules. The incoherence of these systems often leads to a conflict of institutional prescriptions, which increases the uncertainty for medical staff.

Key Psychiatric Reforms: A Historical Context

Active discussions about the medicalization of mental disorders began in social sciences in the early 1970s. Researchers indicated the growth of psychiatrists’ institutional power in the questions of regulating different spheres of social life. It was claimed that psychiatrists gain political and economic benefits due to the diagnostic manuals — International Classification of Diseases (ICD) and Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) — which “make us crazy” (Kutchins, Kirk 1997). Furthermore, social criticism of psychiatry called into question not only the adequacy of diagnostics’ methods but also the ways of treating patients. Representatives of antipsychiatry movement (T. Szasz, R. D. Laing, F. Basaglia, D. Cooper, etc) paid attention to the numerous occasions of abuse and unsatisfactory conditions of treatment of patients in asylums.

Mostly because of expansion of antipsychiatry ideas the situation began to change. Thus, in the second half of the XX century, the process of deinstitutionalization started. In those cases when the patient’s condition was stable and the observation on him was not required, the opportunity of ambulatory psychiatric help was realized. In 1970s as a result of the reforms more than a half of the patients in asylums of Europe and the USA were on the outpatient treatment, out of permanent control from hospital staff.

However, it is a well-known fact that in the USSR the situation developed in the opposite direction. In the 1960s — 1980s more and more inpatient hospitals were being opened, the number of psychiatric hospital beds increased by a factor of more than 1,5 (one and a half) from 222.600 to 390.000 (Bloch, Reddaway 1997). Moreover, numerous incidents of illegal restraints in asylums for political reasons got extensive publicity. Reports about the repressive function of psychiatry in the post-Soviet space were received until the beginning of the 2010s (Van Voren 2013).

During the last 10 years, the sphere of psychiatric care in Russia has been in the process of reorganization. The infrastructure of psychiatric services delivery has changed, which influenced the system of opportunities and limitations for medical staff. Since 2010 psychiatric system of Moscow and Moscow region has been experiencing a period of intensive transformations. The most essential changes are connected with the transfer of state psychiatric help to financing through compulsory medical insurance, in the framework of a pilot project to “optimize” mental health care (at the moment it is appropriate only for Moscow region; psychoneurological services in Moscow are provided by multichannel model of financing), installation of electronic systems of the reception’s process, and, at last, massive reform of institutions within the framework of the Concept of development of psychiatric service in Moscow under the pretext of deinstitutionalization.

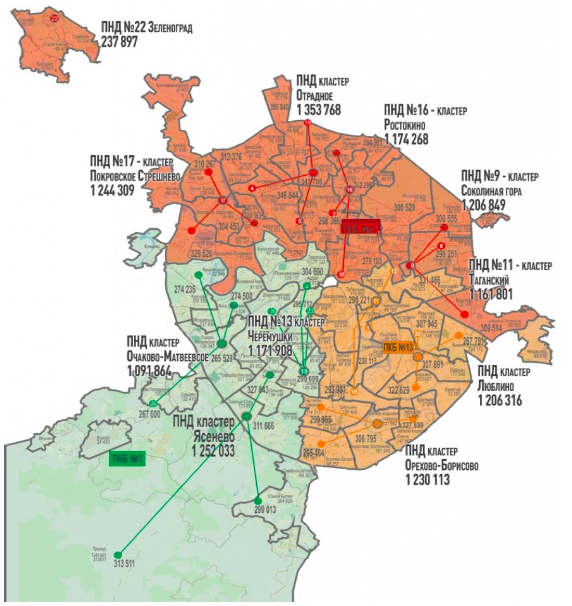

The declared purpose of the reform was twofold: to “unload” asylums and to strengthen outpatient elements of the system. During the reform, the number of asylums was reduced from 17 to 3. Thus, the number of “urgent beds” in asylums was reduced rapidly from 106 psychiatric hospital beds per 100 000 inhabitants to 12.5 per 100 000 inhabitants. Some asylums were merged, others were reorganized into psychoneurological boarding houses and psychoneurological centers (dispensaries) — this type of organization of psychiatric service emerged in the USSR in the 1950s. Nowadays the territory of Moscow is divided into 11 service zones, or territorial clusters: each of them has four psychoneurological centers, each including a one-day hospital.

In 2015, as part of the pilot project, psychiatric institutions in the Moscow region switched from budget funding to the compulsory medical insurance system. The criteria for paying for the services of a psychiatrist were also changed. The established norms specify that there is a single visit (outpatient appointment), paid at the minimum rate, and treatment, which includes at least two outpatient appointments per month. The latter is 2-3 times more expensive. Reception vouchers are regularly sent to the Central Clinical Hospital of the Presidential Administration of the Russian Federation (“Kremlin Hospital”) and are registered in the special electronic system. Based on the results of the control measures, a “coefficient of intensity” is assigned. It is increased or decreased depending on the implementation of the plan of outpatient appointments (state target).

Such high scales of changes have had several important consequences for the work of the professional staff and the functioning of psychiatric service.

Conceptualization

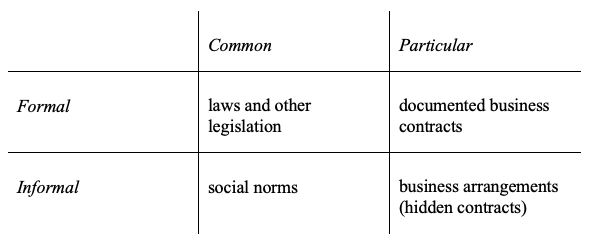

First of all, transformations in psychiatric service in Russia have changed the existing system of informal and formal institutional constraints (North, 1990). In this article, we assume that institutional frameworks of psychiatric institutions are the aggregate of the “rules of the game” in the sphere of state psychiatric service. These rules differ, firstly, by the way of their statement. We define formal rules as written prescriptions, public and obligatory for execution, while informal ones are those not declared openly and concealed from outsiders. Secondly, the rules differ depending on the level of the coverage and are divided into common (or general) and particular ones — either generally known to a professional group, or to the particular kind of the staff only.

Thus, one can distinguish four groups of rules: laws and other legislation refer to the common formal rules, documented business contracts — to formal particular restrictions (rules). General informal rules, which apply to the wide circle of agents, are represented by standards, and informal specific rules — by business arrangements or hidden contracts (Radaev 2001).

Besides, the reorganization of the psychiatric care system in Russia also changed the relational structures between different medical agents. In the first place, one can see the growth of bureaucratic accounting and control of the medical staff by different supervisory instances. There are two ways to differentiate these relations: firstly, by the level of indirectness — whether they are direct or indirect. Secondly, whether they are inner or outer relations, that is, inside a particular organization or outside of it. And, thirdly, whether they are authoritative or collegial.

The change in the disposition of different medical agents has, in turn, changed the governance systems — the mechanisms which “support the regularized control — whether by regimes created by mutual agreement, by legitimate hierarchical authority or by non-legitimate coercive means — of the actions of one set of actors by another” (Scott, et al., 2000: 21) (as cited in (Scott 2007: 30)). The emergence of a new type of player in Moscow regions’ psychoneurological centers — the insurers — as well as a change in the subordination of psychiatric services in Moscow has led to the mix of professional, market and state controls — forming managerial governance mechanisms based on the principles of efficiency assessment and standardization of the public services. These transformations are primarily connected to the growth of bureaucratic accounting and control of the medical staff by supervisory instances.

At present, the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation is the largest single manager and provider of mental healthcare in the country; it is also a controlling agency within the field. The Ministry of Health functions in the absence of free-market mechanisms and the medical community’s autonomy, supervising both the reports provided to insurers (in Moscow region) and the assessment of the effectiveness of reform in Moscow, as expressed in “proper” statistical data.

While these transformations characterize the governance systems outside organizations, they allow us to trace the main changes that have taken place in the psychiatric service.

These institutional changes allow us to raise the following questions: how exactly do the directives aimed at reforming the system function within the framework of local social order of psychiatric organizations? How do they change, on the one hand, relational structures of medical agents within different organizations, and, on the other hand, the way psychoneurological centers’ professionals deal with formal and informal rules.

Methodology

We made a comparative analysis of psychoneurological centers in Moscow and Moscow region in order to estimate the variability of rules and relational structures. The data was collected through semi-structured interviews with professional experts — high- and mid-level healthcare workers. As formal rules in Moscow’s asylums are internally heterogeneous, the sample contains interviews with the staff of psychoneurological centers (including one-day hospitals) from three municipal asylums and the staff from three ambulant modules in Moscow region. In total, 24 interviews were recorded (4 interviews from each institution).

The informants were aware of the goal of this study. They agreed to the use of the data provided in an anonymous and generalized form.

Local Social Orders of Psychoneurological Centers: Conceptual Clarification

• Control parameters: formal vs. informal rules

According to the annual plan of outpatient appointments (state target), the level of standards, which influence the amount of staff’s salary, has increased (taking into consideration the system of financing of psychoneurological centers, compulsory medical insurance, and multiple channel financing). In the case of systematic and significant noncompliance with the state target, the medical worker can be dismissed. In the case of minor noncompliance, the medical worker receives a lower salary.

In Moscow, the reform has led to an increasing control from hospital administrations, which, in its turn, caused emergence of accounting frauds. In order to achieve these new formal parameters in the situation of lack of real patients, medical staff create fake notes about the appointment of patients, so-called “additional entries” (pripiska), for which medical professionals may be subsequently held criminally liable.

In the Moscow region, medical staff sometimes improves their performance indicators through preventive examination of the patient’s relatives who accompany the patient to the appointment. Rarity of “additional entries” cases in Moscow region mainly stems from an intensified control by insurers.

The risk of criminal prosecution increases significantly in the case of “additional entries”, while under-implementation of the annual plan in psychoneurological centers near Moscow does not currently entail the same costs as in psychiatric institutions in Moscow.

Also, it should be noted that there is a significant difference in the payment of one-time and repeated outpatient appointments in the system of compulsory health insurance. The number of appointments influences the salary of medical health workers in Moscow region, or more precisely the amount that is added to the fixed salary rate. However, as our interviews indicate, nobody from the medical staff tried to manipulate these figures in order to receive economic benefits. The staff are more concerned with the parameters set for their psychoneurological center in general, as the reputation of their institution depends on it.

• Compliance with formal rules vs professional ethics

It is not a surprise that realization of the reform of psychoneurological centers in Moscow has led to the intensification of control of the cases of hospitalizations (psychiatric hospital admissions). Medical workers, who were in charge of supervising this reform, were required to submit a report with maximally effective parameters and to show that sharp reduction of the number of asylums and hospital beds was reasonable. The administration transmitted to the staff the following instruction: to limit the duration of stay for patients in the hospital to 30 days and also to minimize or even eliminate the cases of repeated hospitalizations; hospital admission should be carried out no more than once in 3-4 months. If these criteria are not met, the employees of psychoneurological centers got a reproof.

As a result of this reform most patients (especially in dire condition) cannot receive full necessary treatment — as the duration of hospitalization has been severely cut. Consequently, they need repeated hospitalizations. To avoid violation of the proclaimed instructions, some establishments practice repeated hospitalization of patients under different names. In this case, the psychiatrists are guided solely by the needs of the patients, and they disregard the regulations.

On the basis of this case one can introduce additional differentiation between two categories of general informal rules (social norms), depending on the source of these rules: the first category is professional norms, medical ethics requirements; the second category is institutional norms emanating from supervisors. In turn, one can notice that administration of psychoneurological centers took an ambivalent position: on the one hand, they are carriers of professional ethics, on the other hand, they are part of the hierarchical system of “multiple authority or multiple subordination” (Perrow 2013: 957). They are both translators of the requirements of their superiors, “carrier professionals”, and those who must adapt and apply these requirements in practice, clinical professionals (Scott, 2008: 227-228). Different reactions of the heads of psychoneurological centers are related to this ambivalent position.

• Hierarchical structure of psychiatric services: authoritative and collegial relations

The relations between medical staff and heads of psychoneurological centers in the Moscow region can be characterized as collegial. All psychiatrists, including heads of dispensaries, emphasize that their work is based solely on a professional sense of duty, integrity, and respect for their colleagues — without all of these it would not have been possible to carry out many of their duties. While there is certainly a formal hierarchy, it is noted that in difficult work situations, everyone works together.

Another characteristic of the institutional order is related to the change in the conditions of patients’ stay in Moscow asylums. As the state of patients often aggravates, some psychoneurological dispensaries establish the system of hidden agreements: managers of psychoneurological centers tend to “hide” the presence of difficult and aggressive patients. Every member of the staff knows how to behave in such situations in order to solve the problem with minimal costs. Besides, heads of psychoneurological centers are not inclined to punish medical staff for their actions during cases of emergency, even if the health workers’ actions violated the requirements.

Opposite to the cases above, the heads of psychoneurological centers in Moscow who maintain good relations with their superiors pay a lot of attention to their reputation as managers and don’t want to lose it due to non-compliance of their staff with plans and formal parameters. The relations between such heads of psychoneurological centers and medical staff can be characterized as authoritative.

Comparing local orders of different psychoneurological centers, the informants emphasized that compliance of medical staff with professional standards was possible only in the situation of collegial relations inside the organization. On the contrary, in organizations with the authoritative type of relations, the priority is given to institutional norms.

• Systems of governance based on direct vs. indirect relations

There are noticeable differences in the control mechanisms over observance of the rules for psychoneurological centers at different asylums in Moscow. Usually such differences are manifested in the frequency and the nature of work conferences — held in-person or remotely via Skype; with the participation of the staff of a particular dispensary or with the participation of the heads of psychoneurological centers and the heads of hospitals. The medical staff of those dispensaries, where conferences were constantly conducted with the participation of heads of hospitals (direct relations), pointed out that their supervisors were focused only on following the formal requirements and were not ready to go deeply into their working problems. On the contrary, the medical staff of those dispensaries where such conferences were rarely or not conducted at all (indirect relations) assessed their supervisors as understanding and ready to discuss difficult cases.

The psychoneurological centers in Moscow region enjoy greater autonomy from hospitals (as compared to Moscow dispensaries): the control of the work of psychoneurological centers’ staff happens only through statistical reports to the supervisory instances. Despite frequent inspections of insurers, the medical staff of psychoneurological centers in Moscow region tend to pay less attention to full compliance with the required standards as compared to similar Moscow institutions. Control mechanisms for Moscow region dispensaries do not imply direct interaction between the administration and its superior organizations. This positively correlates with the existence of collegial relations within individual organizations and the crucial importance of professional norms for the medical staff.

Conclusion

This article continues a long and respectable tradition of medical sociology research that began in the 1920-30s (Bloom 2005; Cook, Wright 1995). With the formation of powerful state institutions that followed the formation of professions in the U. S. and the UK (Scott 2008), the interest of sociological research shifted from the relationship between doctor and patient to a variety of institutional actors, commercial and bureaucratic models of health care delivery (Bloom 2002; Goss 1963), non-medical influences — such as availability and types of patients’ health insurance (Mechanic, McApline 2010; Mckinlay, et. al. 1996), or their social status (Wright, Perry 2010) — on clinical decision-making. Since the 1960s, which Friedson (2001) identified as the end of the “golden age” of physicians’ autonomy, the sociological inquiry has focused primarily on the political influence and competition between different players. The scrutiny of medical institutions that followed this fundamental shift posed many questions to social researchers: about the relationships between organizations, the similarities and differences in their local social orders, the arrangement of “multiple authority or multiple subordination”, and the relationship between formal and informal structures.

Instead of focusing on the impact of an institutional force on the organizational field and proceeding from the uniformity of medical rules, practices and structural isomorphism, we addressed the differences in local social orders. As can be seen from this study, firstly, institutional forces are heterogeneous, and secondly, different organizations may react differently to the same imposed rules. Even the application of the same strategy and tactics (Oliver 1991) in response to institutional pressure may vary for different organizations.

Now we can give the following answer to the research question: psychiatric reforms have changed the configuration of relations between different medical agents outside individual organizations. However, in the case of intra-organizational relationships, institutional pressure of the reforms has served only as a litmus test, revealing the correlation between, on the one hand, relations between medical staff and heads of psychoneurological centers, and, on the other hand, frequency and nature of contacts between administration of psychoneurological centers and the heads of hospitals. The research allowed us to identify the correlation between three variables: direct / indirect relations with supervisory instances, adherence to institutional / professional norms and authoritative / collegial relations within the organization.

However, the conflict of professional and institutional rules, which in this research is embodied in the figure of the head of the psychoneurological center, and its connection to the other aspects of the local order of organizations requires a more detailed study.

References

Paneyah, E.L. (2001) Formal’nye pravila i neformal’nye instituty ikh primeneniya v rossiyskoy ekonomicheskoy praktike [Formal Rules and Informal Institutions of Their Application in the Russian Economic Practice], Economic Sociology, Vol. 2, No.4, pp. 56–68.

Radaev, V.V. (2001) Deformalizaciya pravil v rossijskoj hozyajstvennoj deyatel’nosti [Deformalization of rules in the Russian economic activity], T.I. Zaslavskaya (ed.) Kto i kuda stremitsya vesti Rossiyu? Aktory makro-, mezo- i mikrourovnej sovremennogo transformacionnogo processa [Who wants to lead Russia and where? Actors of macro-, meso- and microlevels of the modern transformation process], Moskovskaya vysshaya shkola social’nyh i ekonomicheskih nauk [The Moscow School of Social and Economic Sciences], p. 253–262.

Scott, R. (2007) Konkuriruyushchie logiki v zdravookhranenii: professional’naya, gosudarstvennaya i menedzherial’naya [Competing Logics in Healthcare: Professional, State and Managerial], Economic Sociology, Vol. 8. No.1, p. 27–44.

Bloch, S., Reddaway, P. (1977) Russia’s Political Hospitals: The Abuse of Psychiatry in the Soviet Union, Victor Gollancz.

Bloom, S.W. (2005) The relevance of medical sociology to psychiatry: A historical view, Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease, Vol. 193. No.2, p. 77–84.

Bloom, S.W. (2002) The word as scalpel: a history of medical sociology, Oxford University Press.

Cook, J.A., Wright, E.R. (1995) Medical Sociology and the Study of Severe Mental Illness: Reflections on Past Accomplishments and Directions for Future Research, Journal of Health and Social Behavior, Vol. 35, p. 95–114.

Fakhoury, W., Priebe, S. (2007) Deinstitutionalization and reinstitutionalization: major changes in the provision of mental healthcare, Psychiatry, Vol. 6. No.8, p. 313–316.

Freidson, E. (2001) Professionalism: The Third Logic, Polity Press.

Goss, M. (1963) Patterns of Bureaucracy among Hospital Staff Physicians. E. Freidson (ed.) The Hospital in Modern Society, The Free Press, p. 170–194.

Grob, G.N. (2016) Community Mental Health Policy in America: Lessons Learned Israel, Journal of Psychiatry and Related Sciences, Vol. 53. No.1, p. 6–13.

Kutchins, H., Kirk, S.A. (1997) Making us crazy. DSM: The psychiatric bible and the creation of mental disorders, The Free Press.

Luft, H.S. (1981) Diverging trends in hospitalization: fact or artifact? Med Care, Vol. 19. No.10, p. 979–994.

Mckinlay, J.B., Potter, D.A., Feldman, H.A. (1996) Non-medical influences on medical decision-making, Social science and medicine, Vol. 42. No.5, p. 769–776.

Mechanic, D., McAlpine, D.D. (2010) Sociology of Health Care Reform: Building on Research and Analysis to Improve Health Care, Journal of Health and Social Behavior, Vol. 51 (suppl 1), p. S147–S159.

North, D. (1990) Institutions, institutional change, and economic performance. Cambridge University Press.

Oliver, C. (1991) Strategic Responses to Institutional Processes, Academy of Management Review, Vol. 16. No.1, p. 145–179.

Perrow, C. (2013) Hospitals: technology, structure, and goals. J.G. March (ed.) Handbook of Organization, Routledge.

Scott, W.R. (2008) Lords of the dance: Professionals as institutional agents, Organization Studies, Vol. 29, p. 219–238.

Scott, W. R., Ruef, M., Mendel, P.J., Caronna, C.A. (2000) Institutional Change and Healthcare Organizations: From Professional Dominance to Managed Care, University of Chicago Press.

Szasz, T. (2007) The Medicalization of Everyday Life: Selected Essays, Syracuse University Press.

Van Voren, R. (2013) Psychiatry as a Tool for Coercion in Post-Soviet Countries, European Parliament.

WHO (1997) European Health Care Reform: Analysis of Current Strategies, WHO Regional Publications.

WHO (2003) Organization of services for mental health, World Health Organization.

Wright E.R., Perry B.L. (2010) Medical Sociology and Health Services Research Past Accomplishments and Future Policy Challenges, Journal of Health and Social Behavior, Vol. 51 (suppl 1), p. S107–119.